La Candlemas, the story of a party with great suggestions that has its roots in pre-Christian rites linked to the triumph of light. Let’s find out what it symbolises for the faithful and why.

La Candlemas, the story of a party with a thousand shades. The feast of Candlemas, celebrated by Catholics on 2 February has taken on gradually different meanings over the centuries.

Born as a Marian celebration, it evoked the Purification of the Madonna, but later became a Christological festival focused on the figure of Jesus and his recognition as the Savior of the world.

No less important is the popular dimension of this festival, testified by proverbs and customs, linked in particular to the passage from winter to spring that this day represents. To name just a few: “Candlemas, dark of winter, there is no fear“, or “for Santa Candelora if it snows or if we are outside winter“.

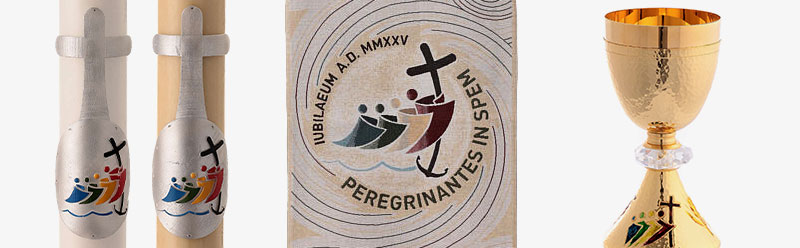

A feast linked to the triumph of light over darkness, as evidenced by the tradition of blessing and lighting tapers and candles, but also a symbolic passage that determines the end of the Christmas holidays and the beginning of the Easter journey.

La Candlemas, the story of a festival with many religious and symbolic meanings, which we hope to help you discover.

Why lighting up a candle in church?

Lighting up a candle in church is a tangible sign of faith. From the baptism candles to votive candles, light as a symbol of…

Why is it celebrated and when

Candlemas is a popular term used to remember and celebrate the day of the presentation of Jesus in the Temple of Jerusalem. In fact, according to the law of Moses, parents had to accompany the firstborn males to the temple, forty days after their birth, to officially present them. Our Lady and Saint Joseph were no exceptions for little Jesus, and forty days after Christmas they took him to Jerusalem.

This episode in the life of Jesus is told by Luke (Luke 2:22-39) and is celebrated by the Catholic Church on 2 February, but it is also celebrated by the Orthodox Church and some Protestant churches.

According to Luke, on the occasion of the Presentation of Jesus in the temple, an old man named Simeon, who had long awaited the coming of the Messiah and had been promised by God that he would not die without seeing him, saw the baby Jesus, took him in his arms and he said, “Now, O Lord, let your servant

go in peace according to your word; for my eyes have seen your salvation, prepared by you before all peoples, light to illuminate the nations and glory of your people Israel.” (Luke 2:29-32)

In practice, Simeon recognised Jesus as the long-awaited Messiah. But his revelations don’t stop there. Addressing Joseph and Mary, amazed by his gesture, he continued saying: “He is here for the ruin and resurrection of many in Israel, a sign of contradiction 35 so that the thoughts of many hearts may be revealed. And you yourself a sword will pierce your soul.”(Luke 2:34-35)

A prophetess, Anna, daughter of Fanuèle, who arrived at that time, in turn, began to praise God and to speak of the child as the Redeemer.

The curious name that the feast has taken is because, on the occasion of this celebration, candles are blessed, which are then distributed to the faithful. These candles represent Jesus the light of the world, paraphrasing the words that the old Simeon pronounced taking Jesus in his arms: ” My eyes have seen your salvation, prepared by you before all peoples, light to illuminate the people and glory of your people of Israel. ” (Luke 2:30-32)

Originally the feast of Candlemas was called Ipapante, a Greek term that means meeting, referring to the meeting between the Holy Family and Simeon and Anna at the temple. It is attested since the fourth century, in the East, and subsequently, thanks to Pope Sergio I, it also spread to the West. It was celebrated by lighting candles and candles in abundance.

The dimension of the encounter with Jesus remains a very important element of this feast. The presentation of Jesus in the temple coincided with his recognition by Simeon and Anna, two people who have always waited for his coming. But there is also the revelation made to Mary, the prophecy regarding the future of her son, and the immense pain she will have to feel, that sword that will pierce her soul.

History

Like many religious holidays, Candlemas has also evolved. We can talk about Candlemas, the story of a festival that brings together many different festivals and traditions.

In the past, before the liturgical reform that followed the Second Vatican Council, the feast of Candlemas was called the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary. This definition, however, completely ignored the origin of the feast, namely the presentation of Jesus in the Temple and the meeting with Simeon, who first acclaimed him as the light of the world.

The choice of the name Candlemas instead derives from previous rites, from the similarity of the practice of the Skylight in the evening of the Roman rite, which involved the lighting of a lamp at sunset to symbolise the light of Christ that defeats darkness and sin.

But it is also likely that this festival derives from pre-Christian celebrations that had the triumph of light over darkness as their common denominator, and consequently involved the use of torches and lamps.

Let’s think of the Roman tradition of the Lupercals, with their purifying torches. The Lupercals were held in February, which for the Romans was very important from a religious and symbolic point of view, as the last month of winter. In particular, it was dedicated to the rites of purification and fecundity, so much so that the Latin verb februare, “purify”, gave its name to the month. The same verb also derives from the name of an Etruscan god of the underworld, Februus, who was venerated with sacrifices at this time of the year.

Also in the Roman world on the calends of February (in the first days of the month) the Goddess Februa, or Juno Februata, was celebrated, in whose honour torches were lit.

Another ancient festival similar to Candlemas is the Celtic festival of Imbolc, which sanctioned the transition between winter and spring, between darkness and light.

The purification of Mary

We mentioned in the previous paragraph how until the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), but still today due to the extraordinary form of the Roman rite, the feast of February 2 was called the Feast of the Purification of the SS. Virgin Mary. According to Jewish tradition, a woman was considered unclean for forty days following the birth of a male child. At the end of this period, during which he could not touch anything sacred or enter the sanctuaries, she had to go to the temple to purify herself.

Here is the reference to the purification described in Leviticus: “When a woman becomes pregnant and gives birth to a boy, she will be unclean for seven days; she will be unclean as in the time of her rules. And on the eighth day let him be given circumcision. Then she will remain another thirty-three days to purify herself of her blood; he will not touch any holy thing and will not enter the sanctuary until the days of his purification are completed” (Leviticus 12:2-4)

The Feast of the Purification of the SS. Virgin Mary sanctioned the end of the Christmas celebrations and opened the new liturgical period for Easter.

Liturgical candles: when and why they are important

Light has always had a very deep and essential meaning for men. There is no religion that hasn’t made it a key element in its…

This tradition linked to the purification of the Madonna spread above all in the West, at least up to the liturgical reform decreed by the Second Vatican Council, which instead wanted to shift the centrality of the rite from the mother to the Redeemer Son, Light of the World. From a Marian vision to a Christological vision, therefore. However, the memory of the Candlemas feast remains in part as a feast of purification in some popular customs. For example, in the Sicilian village of Chiaramonte, women go up to the top of the mountain, the day before the party, and purify themselves with dew.

19 March 2025

19 March 2025